Doctors treat some COVID patients at home because Alabama hospitals are running low on beds

Dr Blake Gibson works on the front lines of the COVID pandemic in UAB Hospital’s Emergency Department, where she sees some of the state’s sickest patients.

But as beds fill up in the UAB and across the state, Gibson and her colleagues are increasingly sending some of them home as part of a program designed to treat border cases outside the hospital. UAB purchased inexpensive pulse oximeters that could be sent home with patients and allow them to monitor oxygen levels remotely, saving hospital beds for patients with a disease. Doctors follow up by phone or video call within 24 hours and frequently afterwards to ensure that the patient’s condition does not get worse.

Gibson said the program was modeled after a program developed at Weill Cornell Medicine in the spring, when hospitals in New York suffered an influx of COVID patients. Gibson said she and her colleagues select low-to-moderate-risk patients and the resources to follow-up on doctor visits.

“What we’re doing is sending them home with a pulse oximeter,” Gibson said. “We teach them how to use the devices when they leave. We teach them about the portable saturation test. We give them protocols on when they might need to return to the emergency department.”

The pandemic is forcing UAB and other medical service providers to make the most of hospital resources. Patients who do not require mechanical ventilation may not benefit much from their admission. Treatments such as remdesivir given to hospitalized patients have not been shown to reduce mortality rates.

The pulse oximeter can identify patients who are not getting enough oxygen and needing treatment in the hospital. Robin Scott, a nurse practitioner in Marshall County, has treated many patients at home with pulse oximeters and, in some cases, with portable oxygen.

Before COVID, she said she would always send patients to the hospital when their oxygen levels drop below 90. Now she has learned to manage some of her patients at home with portable oxygen. I started ordering oxygen and breathing treatments for some patients who refused to go to the hospital.

Scott said, “They are terrified.” “They are so terrified of this virus and the ventilation and the death that is very scary for them.”

Scott’s team members are closely monitoring COVID patients.

“I have staff,” Scott said. “If someone is very sick, they call them every day.” “For the most part, we’ve had tremendous success keeping them out of the hospital.”

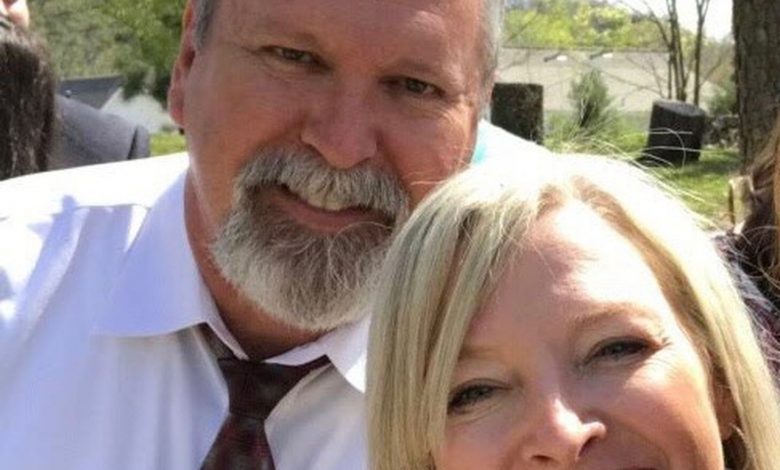

Leslie Wright and her husband, Mark Hopper, contracted the COVID disease in November. Scott trained Wright during her illness at home, checking frequently and prescribing medications to treat various symptoms.

When Wright recovered, her husband became sicker. Scott brought him to her clinic for intravenous fluids and breathing treatments. I sent an X-ray technician home with a portable device to check his chest. His oxygen levels continued to drop and Scott determined he had pneumonia in both lungs.

Wright said, “I came and said, ‘We need to go to the hospital,” and he said, “Who are you? “

Hopper was hospitalized for five days, where he received remdesivir and made a full recovery.

“The one thing about a doctor who is in constant contact with us is that she knows what to do,” Wright said. “Maybe I wasn’t thinking as clearly as I would normally. Just having that support made us feel more supported.”

Dr. David Thrasher of Montgomery Pulmonology has treated patients both in and out of the hospital. And he is pushing for better treatments early in the illness to prevent hospitalization. Although many patients recover without treatment, it is believed that treating more people early in the disease can prevent hospitalization and death.

“As I have said for many months, I think we should treat these patients earlier rather than later and do our best to keep them out of the hospital,” Thrasher said. “Once they enter the hospital, our options are very limited.”

Thrasher treated the first patient in Alabama hospitalized with the COVID-19 virus. In the months that followed, he modified his treatment regimen to improve results. He hopes that monoclonal antibody treatments will keep more patients at home, as they can be given outside of the hospital.

Many of the patients he now observes at home using portable oxygen and pulse oximeters would have been hospitalized during the summer. Thrasher said it is crucial to closely monitor patients for signs that they are not getting enough oxygen.

“I’ve got oxygen for many of the patients for home use rather than putting them in the hospital,” Thrasher said. “This should be monitored very carefully, and I ask my patients to check the pulse oximeter at least three times a day and inform me if their saturation drops. This is labor-intensive, but I think it is paying off as we keep more people out of the hospital.”

Gibson said patients who struggle to breathe may still need hospital treatment. As doctors learn more about the virus, they are better at identifying patients at greatest risk.

“A lot of this is new,” Gibson said. “We are learning as we move forward and trying to ensure that we are taking advantage of lessons previously learned from the pandemic to use our resources in the most responsible way.”

“Food expert. Unapologetic bacon maven. Beer enthusiast. Pop cultureaholic. General travel scholar. Total internet buff.”